Mental Health: Reclaiming the Language

November 2024

Sondos Al Sad

“Stigma is a process by which the reaction of others spoils normal identity.”

Erving Goffman

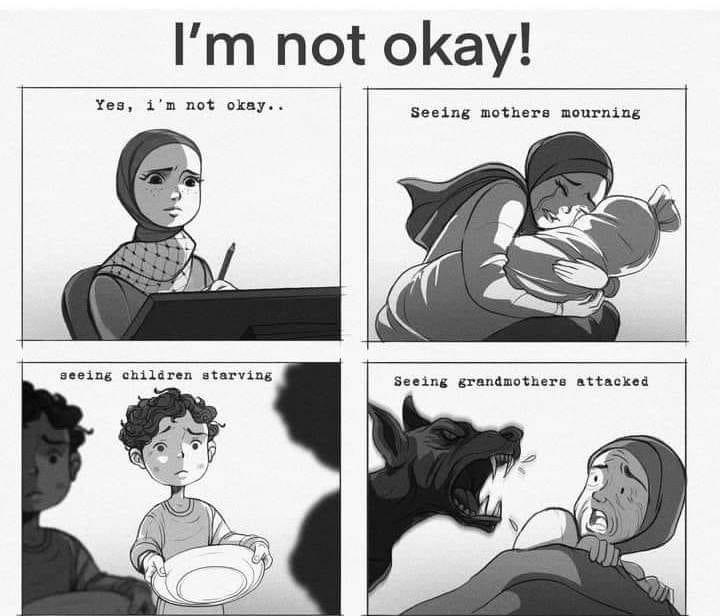

When we talk about the “stigma” of mental health in the Muslim community, we often overlook a crucial factor: the healthcare landscape itself. Instead of addressing the root issues, we focus on superficial solutions, using jargon that only academic experts might find appealing.

For many, especially those who don’t speak the dominant language, expressing mental health concerns can feel overwhelming. The system often dismisses their voices, adding to their emotional burden.

Language is powerful.

In today’s diverse world, especially in immigrant-rich regions like the global North, we must go beyond dry, literal translations in healthcare. Choosing the right words can break down barriers, enhance education, promote genuine cultural exchange, and make healthcare more cost-effective.

Secular psychology has its limitations, particularly when it tries to exclude spirituality and religiosity from its discussions. Ignoring these spiritual frameworks in mainstream training creates a gap between Muslim patients and providers and the broader healthcare system.

Terms like “Fitra” (innate disposition), “‘Aql” (intellect), “Nafs” (self), “Ruh” (spirit), “Salah” (prayer), “Tazkiyah” (purification), and “Adab” (manners) carry deep meanings that are often lost in translation. Engaging with these terms can bridge the gap between Muslims and the healthcare landscape.

It’s easy to get caught up in sophisticated language, asking questions like “Why don’t Muslims seek mental health services?” or “Why is mental health stigmatized?” Instead, we should ask, “What are the shortcomings in today’s psychology that prevent it from meeting the needs of diverse communities?” and “What is missing in psychology training that’s keeping it from making the world a safer, better place, despite technological advances?”

In these challenging times, holding onto our vocabulary is a form of cognitive resilience against the erasure that’s becoming common in biomedical training.

Step up for those in the biomedical field—whether you’re writing, practicing, or training—. Use language that’s true to the communities you serve. Stay authentic to your oath to “do no harm” and “do justice” to those who seek your advice.

Be a beacon of truth, your truth.